Article Contributed By Dr Felicia Low, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, Department of Communications And New Media, Faculty of Arts and Social Science

Arts practices with communities have become popular and sought after amongst independent artists, arts and social organisations in Singapore over the past decade. There is a genuine wish to make arts practices socially relevant across different sectors, such as education and healthcare. This wish is matched with a genuine search for engagement practices which are both responsive and ethical to the needs and contexts of the ground.

The search for meaningful and impactful arts engagement practices with communities is not very much different from Research and Development practices of other academic disciplines. Educational sectors, for example, have long included a variety of methods to study pedagogical approaches and the effects they have on student learning. However, because the arts and its forms of engagement are myriad in their approach and conduct, fixing one method, or one way of conducting research on arts engagement with particularistic communities is a foolhardy endeavour. A dance, visual art or drama programme conducted with at-risk youth would require different versions of research tools, and different ways to analyse data, which could include artistic expressions produced by the community, along with its quantifiable effects on self-esteem or confidence. This poses a problem amongst artists and institutions - how can we account for the significance, or benefits, that the community experiences from arts engagement? More urgently, how can we identify quality arts engagement practices which bring about the most significance and impact for particularistic communities?

Inventiveness of Research Design

From past experience, research designed to evaluate arts engagement with communities tend to borrow from many other disciplines. Surveys to record post experience satisfaction are derived from customer service sectors. Clinical pre and post scales used in Psychology or Healthcare are also applied to any arts programme to present evidence of participant impact. These quantitative approaches look numerically impressive in presentations. However, they are seldom able to explain how the arts programme impacted on the participants - was it selection of the artwork used, the quality of facilitation, the music used? These validated scales also tend to track life practices and opinions that are too dispersed in terms of scale items, to be aligned to short termed arts programmes and its effects. Determining one’s resilience to life’s challenges after a short 8 hour arts programme can produce subjective and inaccurate co-relational results.

This latter concern can be addressed with more qualitative methods which artists, anthropologists and educators are familiar with. Observational studies of cause and effect, be it through the experimentation with materials, testing of a new social practice with the community or action research on a new pedagogical approach in teaching are common across their relevant sectors. Rigour is needed in the development of the observational tool used for a particular project with a particular group of people. Observational rubrics need to be designed, tried and tested together with industry partners, to determine if whatever is identified as an observational factor of significance is indeed responding to the needs and context of the community.

This requires time and effort on the part of the artist, researcher and stakeholder organisation, to be willing to return to the drawing board whenever necessary in order to ensure alignment and co-relation between the research tool, the data it can gather and the type of evidence it can produce for the community context. Researchers Fancourt and Poon (2015) for example, have proposed a methodical approach to the development of observational tools that evaluate performing arts activities in healthcare settings. Together with a matching set of interview questions for participants and stakeholders, a more wholistic picture of what exactly the arts programme did, in what way, and for whom, starts to emerge with more clarity.

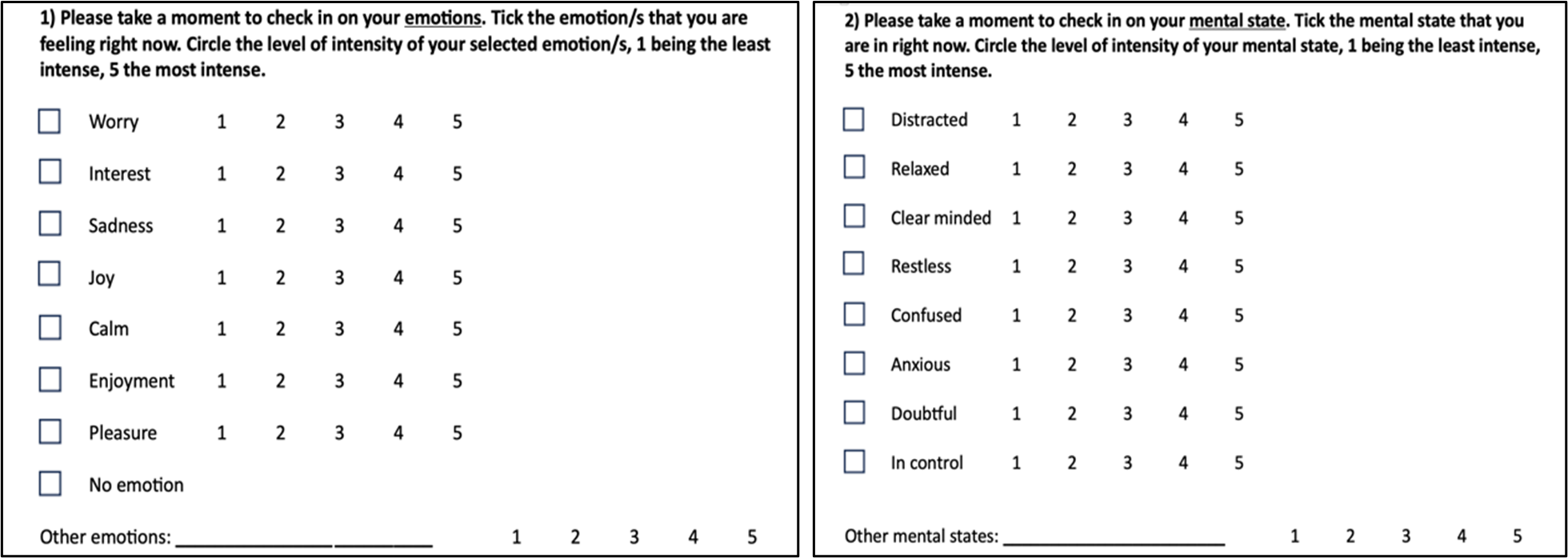

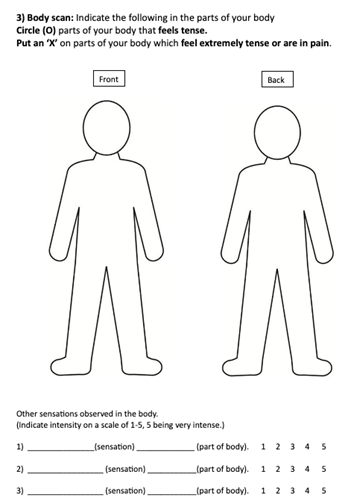

The above process however can be tedious and cumbersome for the context of a hospital, where nurses have more urgent matters on hand, then to spend time observing patient behaviour. Benchmarking across stakeholders is also a challenge. Rather than throw out any possibility of evaluation, some kind of designed compromise could be proposed. Clinical generalised scales could be adapted to correspond to the arts experience of the community. Lengthy validated clinical scales could be shortened based on specific survey items which the arts programme engages with. While the adapted scale may not correspond to ’gold standard’ of randomised control trials used by clinical disciplines, the self-report responses gathered would give a clearer indication of the cause and effect, and hence impact of the programme. This indicative result would have to be supported by interview responses from the participants and the facilitator. It could also be supported by writings, drawings or sharings presented by the participants as part of the artistic process, including the expressed meaning from the artworks or performances produced. This latter forms of data are arts-based research approaches, which validate the arts works in itself as a form of research that can account for the values of the community and how meaning is constructed by the specific community. Below are examples of different tools used to gather data, in order to determine how the Slow Art Guide at National Gallery Singapore provided a space of mindfulness and connection with oneself.

Survey form for participants of the Slow Art Guide (National Gallery Singapore) adapted from the Geneva Emotional Wheel (Version 2.0) and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, after one test run with Gallery staff and research assistants. Details from the Slow Art Guide Research are published with the permission from the Community & Access team, National Gallery Singapore.

Body Scan survey for participants of the Slow Art Guide (National Gallery Singapore). Details from the Slow Art Guide Research are published with the permission from the Community & Access team, National Gallery Singapore.

The Objective - Subjective Debate

Are the results valid? Critiques of clinical quantitative studies question their objective claims as evidence of subjective data cherry picking and lack of co-relation of claimed results to long term effects emerge. Critiques of qualitative data do not defer much from that of quantitative studies. In both cases, a conscientious researcher who leaves no stone unturned, invents the right tool to gather honest data and triangulates her claim with a variety of data sources is the only guarantee of the quality of the research outcome. This is also the researcher who spends enough time on the ground to understand the context and culture of the community, in order to curate a research design which can inspire authentic and insightful responses from the ground. For resource-scarce artists, arts and social institutions who are unable to afford the research fees of academic institutions, partnering with this researcher with the intention to generate applicable research outcomes to community practice is a practical and effective way to present the results of their labour of commitment and hope with the communities they support.

Dr Felicia Low teaches Applied Arts Research and Practice (ACE5409), a course in the Master of Arts in Arts & Cultural Entrepreneurship (MA ACE) programme. To learn more about the MA ACE programme, click here.

Fancourt, D. & Poon, M. (2015) Validation of the Arts Observational Scale (ArtsObS) for the evaluation of performing arts activities in health care settings, Arts & Health.

Shedler J (2020) Where is the evidence in ’evidence-based’ research? in Outcome Research and the Future of Psychoanalysis , (eds) Leuzinger-Bohleber M., Solms M., Arnold E.A. Routledge, London. UK.