Article Contributed By Dr Baey Shi Chen, Lecturer, Department of Communications and New Media, Faculty of Arts and Social Science

Global Fashion and the Environment: An Impending Crisis

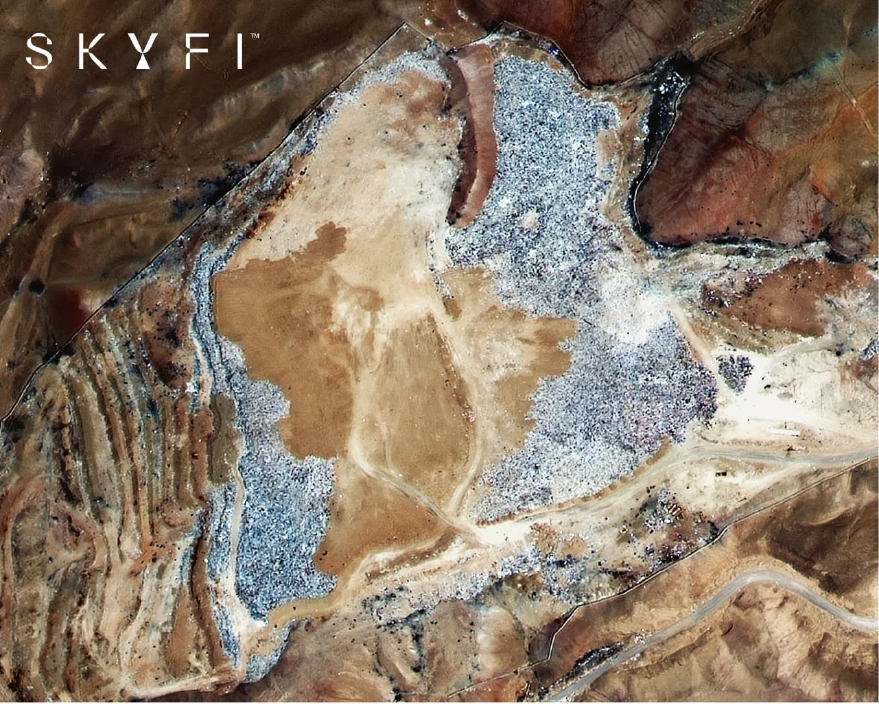

In 2023, the satellite image of a gargantuan pile of discarded fast fashion garments in the Atacama Desert, Chile, was captured by SkyFi, a company specialising in Earth observation data [1]. A powerful visual representation of the human impact on the environment and waste colonialism, the image was a reminder that the failure to recognise the environmental degradation caused by unsustainable fashion production and consumption manifests as inequities across geographical borders [2], and reflected a gap between the professed goals of increased environmental sustainability and the realities of fashion production and consumption.

Visible from space: A landfill filled with unused fast fashion clothes in the Atacama Desert, Chile. SkyFi.

A means to signal both social belonging and differentiation [3], fashion is one of the most visible ways an individual can represent themselves in society. However, clothing is also inextricably linked to the capitalist enterprise, and the relentless pursuit of expressing one’s identity and staying ahead of fashion trends generates an insatiable demand for cheap, disposable clothing that results in the resource-intensive production of clothing. Aside from generating large quantities of textile waste, high levels of pollution that result from unsustainable manufacturing practices related to cultivation, textile dyeing, and finishing processes threaten biodiversity and human health [4]. These challenges exist in tandem with the egregious exploitation of garment workers in the Global South [5], while the perceived hypocrisy of greenwashing by major fast fashion conglomerates has caused advocacy efforts around fashion sustainability to be viewed with a cynical eye by consumers. Collectively, these have culminated in a “wicked problem” ridden with complexity, and it is this challenging milieu that creative practitioners must contend with while leveraging their skillsets to contribute tangible impact. Indeed, with the global fashion industry sitting at the intersection of technology, sustainability, and social equity, the need for creativity has become more urgent than ever.

Using Creativity to Tackle “Wicked Problems”

To manage what seems like an intractable issue, it is worth revisiting what it means to be creative. According to M. I. Stein, creativity entails deviating from the traditional or status quo, reintegrating already-existing materials or knowledge, and is perceived as tenable, useful, or satisfying by a group at some point in time [6]. The last of the points is perhaps the most pertinent — with the global fashion industry fast approaching an inflection point in dealing with the climate crisis and environmental degradation it causes, creative solutions that directly address the needs of the present are urgently needed. Indeed, as much as “creativity for creativity’s sake” remains a core priority, it is now imperative to consider the environmental impact of creative endeavours and recognise that sustainability and social equity must be integral to the strategic outcomes of creative expression and enterprise.

Singapore: Enabling Cultural and Environmental Sustainability

Situated at the centre of an intricate transnational network of production and consumption, Singapore is uniquely poised to contribute to this new paradigm. An emerging generation of fashion designers and cultural producers — already knowledgeable and invested in how their enterprises impact energy consumption, pollution, waste, and labour relations — is engaging with various aspects of conscious fashion to generate more eco-friendly and equitable outcomes for both the local and regional communities. For instance, sustainable womenswear brand Esse emphasises the use of organic and biodegradable fibres for its small-batch designs and ensures fair remuneration and safe workplaces for its regional production partners, while heritage textile specialist OliveAnkara abides by a zero-waste philosophy in the production of its garments.

Photo by Marianne Krohn on Unsplash

Recent policy developments are also encouraging, with increasing support for creative, heritage, and green industries that invite innovative entrepreneurial initiatives that complement Singapore’s infrastructural capacities and aspirations to become a global benchmark for smart, green, and creative cities. Aside from launching the Singapore Green Plan 2030 in 2021 with ambitious goals to green Singapore’s infrastructure substantially, the Singapore government has continued to spotlight the Green Economy as a priority area in its SkillsFuture framework and Skills Demand for the Future Economy Report 2025. The report identifies skills such as sustainability management, sustainability reporting, and carbon footprint management as increasingly critical to the long-term viability of many industries.

A Call to Action

Aside from what these developments imply for the local fashion sector, they also signal a clear need for practitioners across different creative and artistic domains such as product design, music, and film to increase their sustainability literacy and promote sustainable development goals. This calls for professionals who are highly proficient at developing novel, compelling, and values-driven responses to contemporary sustainability problems that can engender eco-friendly and equitable outcomes for their local-regional networks. The NUS Master of Arts (Arts and Cultural Entrepreneurship) programme aims to address this via a new curriculum that enables students to critically examine how creative enterprises can generate fresh ideas and solutions that extend to various communicative platforms and unique experiences that contribute meaningfully to cultural and environmental sustainability.

Furthermore, with the increasing precarity of independent creative spaces in Singapore and other cities, creative entrepreneurship can become a vital form of community-led placemaking that foregrounds a participatory and inclusive approach towards the production of urban and social space [7]. Indeed, the clustering of innovative retail spaces and workshops that prioritise environmental sustainability not only brings creative energy and ethical entrepreneurship visibly and materially into the cityscape, it creates resonant third spaces that allow people to encounter and enact sustainable practices in ways that build vibrant communities and potentially influence public policy in the long run.

Towards Sustainable and Creative Leadership

Prioritising cultural and environmental sustainability in creative enterprise thus reveals a range of interconnected outcomes — not only does it develop innovative business models, communicative responses, and cultural products geared towards reducing environmental impact and promoting social good, it fosters cross-border collaborations and knowledge-sharing that potentially position Singapore and the rest of Southeast Asia at the forefront of thought leadership in sustainability, ethical, and creative entrepreneurship.

The Master of Arts (Arts and Cultural Entrepreneurship) programme at the National University of Singapore (NUS) is a programme that fosters the entrepreneurial spirit of artists and cultivates the business-mindedness required in the cultural and arts sector, not only for artists but also for students aspiring to become arts administrators. The coursework programme provides students with opportunities to discover new ideas for the rapidly developing cultural and arts industry and to introduce established management strategies into the field. The programme will serve as an essential gateway to cultivating the talents required by the art industry.

REFERENCES

[1] SkyFi. (2023, May 10). SkyFi’s satellite image confirms massive clothes pile in Chile’s Atacama Desert. Retrieved August 24, 2025, from https://skyfi.com/en/blog/skyfis-confirms-massive-clothes-pile-in-chile

[2] Agnew, J. (1998). Geo-politics: Re-envisioning world politics. Routledge.

[3] Simmel, G. (1957). Fashion. American Journal of Sociology, 62(6), 541–558. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2773129

[4] Maynard, M. (2013). Fast fashion and sustainability. In S. Black, A. de la Haye, J. Entwistle, A. Rocamora, R. A. Root, & H. Thomas (Eds.), The handbook of fashion studies (pp. 542–556). Bloomsbury.

[5] Dickson, M., & Warren, H. (2020). A look at labor issues in the manufacturing of fashion through the perspective of human trafficking and modern-day slavery. In S. B. Marcketti & E. E. Karpova (Eds.), The dangers of fashion: Towards ethical and sustainable solutions (pp. 103–124). Bloomsbury.

[6] Stein, M. I. (1953). Creativity and culture. Journal of Psychology, 36. 311–322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1953.9712897

[7] Lefebvre, H. (1996). The right to the city. In Writings on Cities (pp 147-159). Oxford Blackwell. (Originally Published as Le droit à la ville).